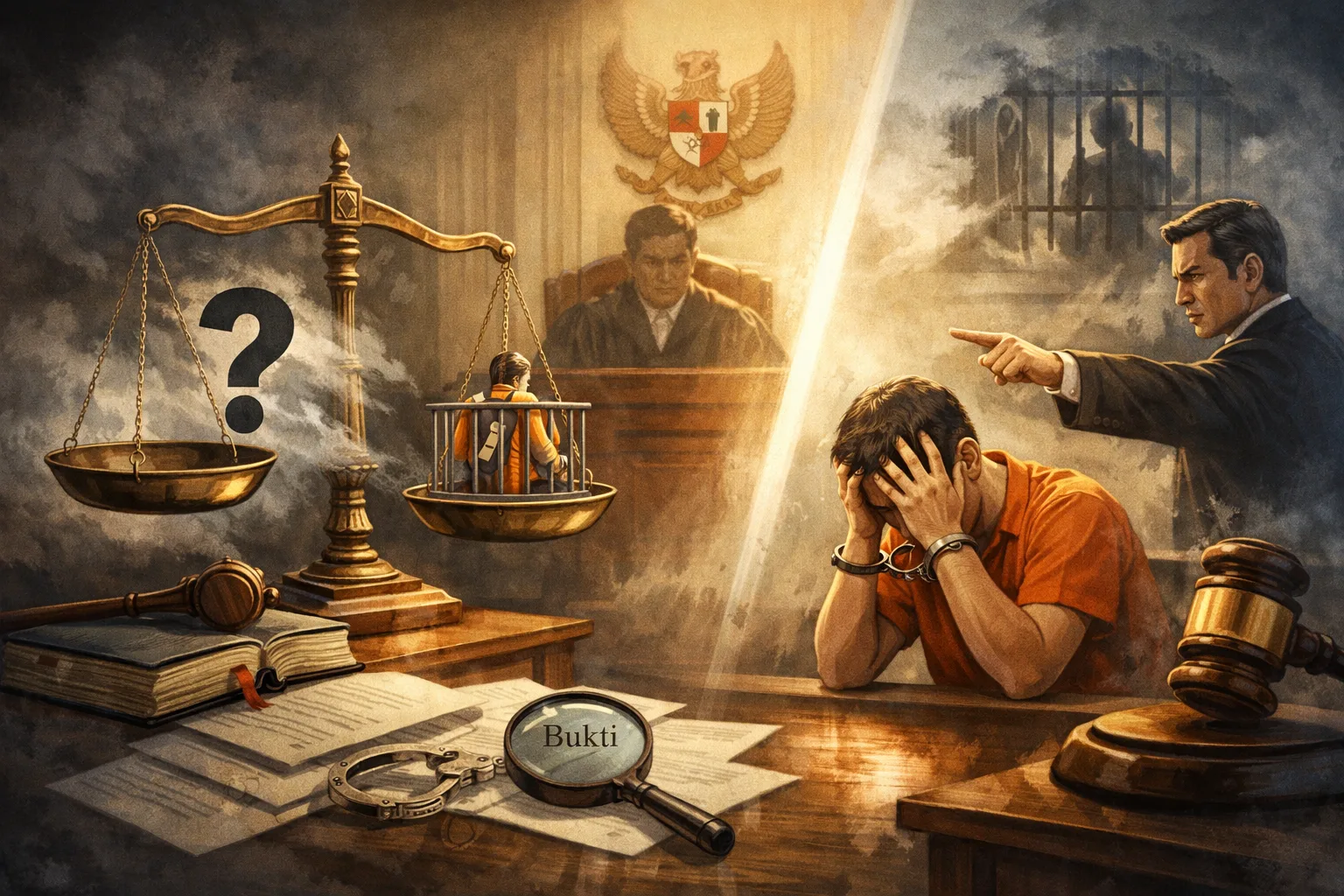

Legal Literacy - We have succeeded in building perhaps the most complex and expensive democratic procedure in the world, only to watch the winners take turns wearing orange vests. This is the greatest irony in our two decades of local democracy: Local elections feel increasingly "democratic" procedurally, but the quality of leadership they produce is often stagnant, if not declining sharply.

We celebrate the right to vote with great fanfare, but at the same time, we ignore the bitter reality that the sovereignty we are proud of is often sold off in the electoral black market long before dawn on polling day.

Every time this five-year cycle approaches, we are again trapped in an outdated debate: should we return to elections through the Regional People's Representative Council (DPRD) or maintain the exhausting direct local elections? Unfortunately, this debate often becomes a dead end because we are too busy arguing about "who votes", that we forget to question "how power is controlled" and "what are the real results for citizens" who pay dearly for the party with their taxes.

Direct Local Elections and the Decline of Local Democracy Quality

The fundamental concern in our current democratic practice is the birth of what I call "Democracy Procedure Fetishism". We have sanctified the ballot box as if it were a sacred object that would automatically radiate legitimacy and prosperity. In this reasoning, direct local elections are considered identical to people's sovereignty.

In fact, if we borrow the lens of legal realism, the glorified sovereignty is often just a commodity traded through networks of clientelism and patronage. As sharply observed by Aspinall & Berenschot (2019: 45), electoral relations in Indonesia have long been besieged by the power of capital that dictates the direction of regional policy.

Citizen participation in the polling booth is often not a reflection of a rational choice of work programs, but rather the result of identity mobilization or simply short-term material transactions. When electoral legitimacy is no longer directly proportional to the quality of governance, then the election procedure has actually failed to fulfill its functional mandate. It becomes a procedure that is very democratic formally, but produces oligarchic power practices substantially.

Fiscal Burden of Direct Local Elections and Damaging Political Costs

The issue becomes increasingly urgent when we juxtapose the idealism of democracy with the suffocating fiscal reality. The budget allocated by the state to organize the 2024 simultaneous regional elections (Pilkada), for example, reaches a fantastic figure of around IDR 28 trillion. This figure is not just a series of zeros on paper; it is a very real opportunity cost for national development.opportunity costImagine, with that much money, the state is mathematically capable of building more than 1,400 modern type C hospitals in remote areas, or financing full scholarships for millions of the nation's children to pursue higher education for four years. We need to honestly ask: is this giant cost really an investment to improve the quality of leadership, or is it actually the main fuel for political corruption after being elected?

Jimly Asshiddiqie (2019: 112) has warned that the high political cost of winning direct regional elections inherently creates a need for candidates to make a "return on capital" through misappropriation of the APBD (Regional Budget) or abuse of authority in licensing. Our democracy has become expensive not only because of the technicalities of its implementation, but because it finances a system that undermines the integrity of its own public officials from the first day they take office.

←

Comments (0)

Write a comment