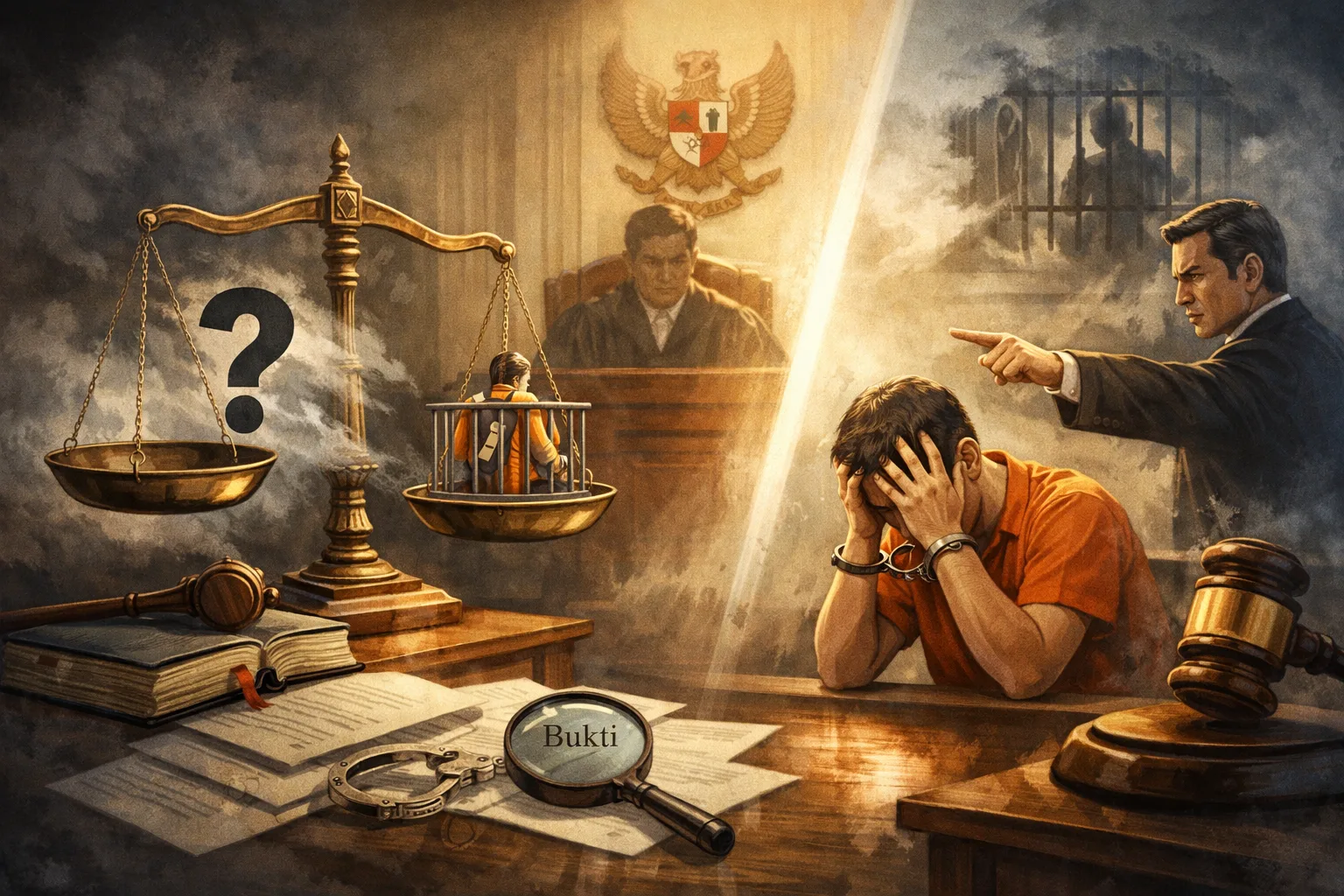

Legal Literacy - Corruption law enforcement in Indonesia lately presents a disheartening anomaly. On one hand, television screens are filled with rows of orange-clad suspects looking dejected. However, upon closer examination of the verdicts and the list of names involved, we will find a peculiar pattern: those sitting in the defendant's chair are generally technical implementers, Commitment Making Officials (PPK) who are trapped in administrative matters, or field staff who are simply carrying out orders.

Meanwhile, structural actors—including policy controllers and intellectual actors at the top of the pyramid—often remain beyond the reach of legal radar, or at most are only summoned as witnesses who suddenly develop amnesia. This is the phenomenon of "corruption without prison" for those in power in the structure; a form of normalization of impunity that slowly creeps through the cracks of procedural law and increasingly mechanistic law enforcement techniques.

Selectivity of Law Enforcement

The public's anxiety today no longer lies in the fact that corruption exists, but rather in the increasingly blatant selective enforcement. There is a strong impression that our law enforcement is having a "field day" at the expense of the small fry, while rolling out the red carpet for the elite. This inequality is not merely a matter of the morality of officials or the personal integrity of prosecutors and judges, but is rooted in inherent defects in our legal design and prosecution politics. We are trapped in a legal paradigm that worships documentary evidence and administrative formalities, but is at a loss when faced with asymmetrical power relations.

The Trap of Administrative Paradigm

In many cases of corruption in the procurement of goods and services or natural resource permits, the legal instruments used are often very technocratic. Law enforcers tend to pursue obvious procedural violations, such as errors in determining the winning bidder or deficiencies in the volume of work that are technical in nature.

Herein lies the trap. Structural actors who give verbal instructions, secret codes, or through meetings in private rooms untouched by surveillance cameras, are automatically protected by an administrative fortress. According to Romli Atmasasmita (2018: 45), our legal system tends to rigidly separate administrative and criminal responsibility. As a result, "policy" is often considered an area immune to criminal touch, even if the policy is born from the evil intent (mens rea) to enrich oneself or a group.

Failure to Read Structural Crimes

The logic of law enforcement that targets technical actors is actually a form of failure to read corruption as a structural crime. When the law is only able to ensnare document signers, but fails to touch the intellectual actors who ordered the signing, then the law is actually facilitating the regeneration of corruptors. These policy controllers will easily find new "scapegoats" for the next project, while the corruption scheme remains intact. This confirms Satjipto Rahardjo's view (2009: 112) that the law often loses its penetrating power when faced with established power structures, because the law is forced to work within the boxes of formalities that they create themselves.

Comments (0)

Write a comment